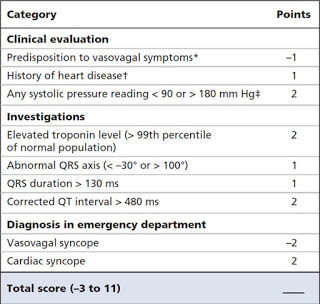

| These authors used data that came from a large multicentre study that developed the Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS). They enrolled consecutive adult patients who presented within 24 hours of a simple syncopal episode. They collected data on baseline characteristics and were eventually able to risk stratify patients by using their newly derived syncope score into low, intermediate and high-risk groups. |

The 30 day follow up was a tremendous undertaking. They had structured review of all available medical records, subsequent visits, hospitalisations, and deaths. They performed a scripted telephone follow up at 30 days and they looked at administrative records for subsequent visits.

A whopping 5581 patients were analysed. As expected, only a small number 7.5% had serious outcomes. The syncope score seemed to work pretty well. The low risk group had 0.4% 30-day arrhythmic outcomes. The intermediate and high risk were 8% and 25% respectively.

The authors state that one-half of arrhythmic events were identified within 2 hours of ED arrival in low risk patients and within 6 hours in the intermediate and high-risk patients.

Based on this, the authors suggest either 2 or 6 hours of cardiac monitoring is enough after syncope but outpatient cardiac monitoring for 15 days in higher risk patients.

There were a few problems…

Only 11% of the patients were hospitalised and the median ED length of stay was only 4 hours. It is no surprise that they found half of the events early on when they were actually looking. It is quite possible that many events were missed when the patients were not being monitored at home. However, they should have at least they should have picked up on mortality.

Remember the extraordinary work they did in assessing the 30-day outcomes? Unfortunately, quality of data is often inversely proportional to the effort and complexity in obtaining it. In other words, they may have been making conclusions based on bad data. It’s hard to know.

There have been several attempts at creating a clinical decision instrument for syncope. Unfortunately, these instruments don’t tend to work in complex disease processes. The CSRS has not been externally validated nor compared to clinician gestalt.

What’s the take home point?

From an evidence-based medicine standpoint, I don’t believe this single study is enough to justifiably change practice. But in our hearts, we all know that low risk patients probably don’t need to be watched very long… and high-risk patients need to be monitored longer. 2 or 6 hours? Who knows…

Covering

Thiruganasambandamooooorhylinglangadong, V, Rowe B, Sivilotti M, et al. Duration of Electrocardiographic Monitoring in Emergency Department Patients with Syncope. Circulation 2019;139:1396-1406. [link to article]

| Dr Brian Doyle is an emergency physician originally from the United States but now very much calls Tasmania his home. Unfortunately, it will now be a bit more difficult to deport him from the country as he passed his Australian citizenship test a few years ago. (He was able to answer that Phar Lap won the Melbourne rather than the Davis Cup). His main interests are mostly the clinical aspects of emergency medicine but also in education, ultrasound and critical appraisal of the literature. He spends much of his time annoying people to help out with conferences. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed