|

Viet Tran

It’s 4am and you’ve finally had a chance to sit, legs aching. Starved of sunlight as winter hits and the lows hit zero degrees celsius, you wonder to yourself if the aches could be Hypovitaminosis D? The nurse boss comes to you, announcing the impending arrival of a man in his 50s found at the park 3 blocks over, cold, CPR in progress, 10min away.

|

|

The patient, Mr Otzi, arrives and initial obs show;

AB - no spontaneous breaths, BVM in progress (minimal resistance), no recordable sats C - No pulse, cool blue/purple peripheries D - GCS3, pupils fixed, hypertonic & areflexive E - ? So he’s cold. But how cold? Key points to remember when trying to quantify the core temperature include:

|

This is Mr Otzi, the oldest natural human mummy. And our patient.

|

|

|

So How Cold is Mr Otzi? (Classification)

SEVERITY

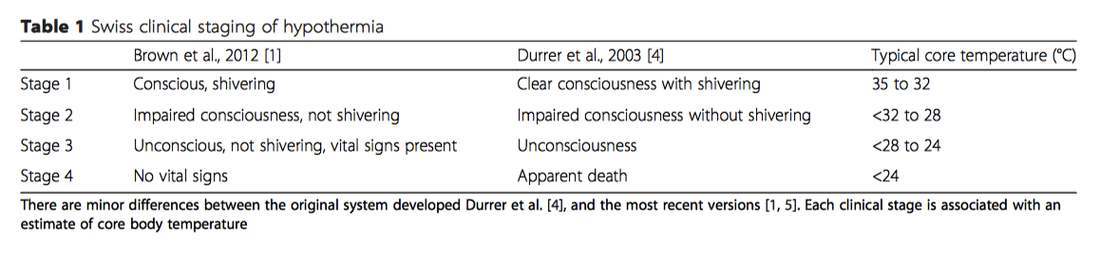

Older textbooks use a classification equating to mild, moderate, severe and profound hypothermia. The problem with this system is that it requires a core temperature.

The Swiss Classification utilises basic vital signs and clinical signs, as is often the limitations in the pre-hospital or 'just arrived' hospital setting. There seems to be reasonable correlation with core temperature (table 1 below),

This classification is important in risk stratifying patients to complications of hypothermia and rewarming techniques.

As always, ensure that hypothermia is not the symptom but the cause. Primary hypothermia refers to the processes outside of the body to reduce core temp. Secondary hypothermia is due to processes internal, either due to dysregulation (eg hypothyroidism, hypoadrenalism, drugs such as alcohol or BZDP, strokes etc) and/or increased heat loss (eg burns, trauma).

1. Brown DJ, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P. Accidental hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1930–8

Effects on the Body

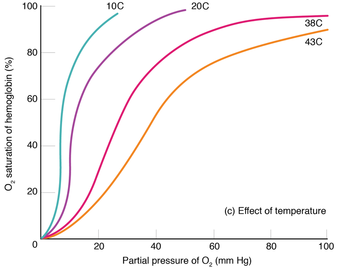

CARDIOVASCULAR

Electrical

The natural progression of rhythm as the patient gets colder is roughly: tachycardia, bradycardia, atrial fibrillation (below 32), ventricular fibrillation (below 28) then asystole

The initial response to falling temperature is a reflexive tachycardia. As temperatures drop further, this then turns into a proportional bradycardia (refractory to atropine & pacing) (1). Atrial fibrillation is not uncommon in patients below 32C (2). It is unclear at what point bradycardia or atrial fibrillation becomes Ventricular Fibrillation, but generally accepted that around 28C that it is within the realms of possibility. The proposed mechanism is that the fibrillation threshold is a lot less, and why rescue-collapse can occur (see below).

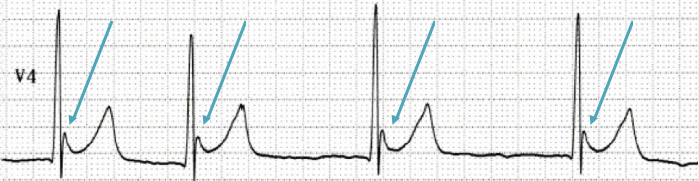

Aside from arrhythmias, J-waves (or Osborn waves) may be present. These are elevations at the junction of the QRS and ST segments (ie the “j-point”). They’re sometimes seen at temperatures below 32C and when present, their height is inversely proportional to temperature. They are by no means prognostic, nor are they pathognomonic (think SAH, hypercalcaemia or even a normal variant). Other ecg findings in hypothermia include: QRS prolongation, Prolonged PR and/or QT interval and Shivering artifact.

Haemodynamic effects are largely intuitive - peripheral vasoconstriction and reduced cardiac output that produces a low MAP that matches BMR and therefore DOES NOT precipitate an imbalanced state (ie shock) (3,4). This is one reason why patients have the best mortality/morbidity outcomes despite potentially prolonged CPR (see management below).

There are 2 haemodynamic phenomena associated with the rewarming process that have become more academic than clinical considerations over time, given the lack of any robust evidence outside of anecdote and animal models.

|

After-drop

In early case series it was observed that some people who were actively rewarmed had an ongoing initial ‘dip’ in their core temperature before rising. The suggested implications of this included an increased risk of VF. There are a variety of academic propositions behind this idea that have gone insofar as being proven by freezing gelatin (5). The bottom line is that it does happen sometimes, but there's a) nothing that we can do about it b) unfounded consequences of its occurrence. |

Rewarming Shock

Rewarming causes vasodilation whereby the cardiac output is not able match, especially if the rate of rewarming is too fast. The bigger case studies for rewarming have not found this to be the case (6,7,8). |

|

AIRWAY/BREATHING

|

CNS

METABOLIC

HAEMATOLOGICAL

|

RENAL

*Is important to consider in the context of early resuscitation |

1. Jacob, Allan I. et al. "A-V Block In Accidental Hypothermia". Journal of Electrocardiology 11.4 (1978): 399-402.

2. Okada, Michio. "The Cardiac Rhythm In Accidental Hypothermia". Journal of Electrocardiology 17.2 (1984): 123-128.

3. Otis AB, Jude J. Effect of body temperature on pulmonary gas exchange. Am J Physiol 1957 Feb;188(2):355-359.

4. Tveita T, Ytrehus K, Myhre ES, et al. Left ventricular dysfunction following rewarming from experimental hypothermia. J Appl Physiol 1998 Dec;85(6):2135-2139.

5. Webb P. Afterdrop of body temperature during rewarming: an alternative explanation. J Appl Physiol 1986 Feb;60(2):385-390.

6. Kornberger E, Schwarz B, Lindner KH, et al. Forced air surface rewarming in patients with severe accidental hypothermia. Resuscitation 1999 Jul;41(2):105-111.

7. Roggla M, Frossard M, Wagner A, et al. Severe accidental hypothermia with or without hemodynamic instability: rewarming without the use of extracorporeal circulation. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2002 May 15;114(8-9):315-320.

8. Roeggla M, Holzer M, Roeggla G, et al. Prognosis of accidental hypothermia in the urban setting. J Intensive Care Med 2001;16:142-149.

MANAGEMENT

|

Be Warned

The caveat to evidence based medicine regarding extreme hypothermia is that many of the success stories evolve from sudden immersion into very cold water or snow and pre-hospital systems that facilitate best practice. Take this into account when considering applicability to your clientele. |

In the prehospital and initial hospital setting, paranoia builds around the idea of Circum-Rescue Collapse. This is the phenomena whereby, due to a low core temp, the heart has a lowered “fibrillation” threshold and even movement can trigger VF. There's no denial of its existence, but recent literature has questioned whether or not this is overstated. This theoretical concern should not delay intubation, central access or transport if clinically indicated.

Advanced Life Support

The varying international resuscitation councils are not consistent with their guidelines;

|

Australian Resuscitation Council/Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (2011)

The latest guidelines for cardiac arrest in special circumstances includes a brief part on Avalanches (page 3, 2011). No position statement on cardiac arrest in the context of accidental hypothermia is addressed. |

|

European Resuscitation Council (2015)

Intermittent CPR If continuous CPR is not possible (eg in the rescue setting), Interrupted CPR can be done; 20-28C 5min CPR/<5min rest, <20C 5min CPR/<10min rest Drugs & DCCV. “It is reasonable” not to give rescue drugs or electricity for T < 30C. For T 30-35C you should double time interval between giving drugs. The reasons are 2 fold:

Bradycardia & Atrial Fibrillation Bradycardia & Atrial Fibrillation should revert with re-warming alone. Bradycardia is usually refractory to pacing and atropine. Ventricular Fibrillation The ERC guidelines send mixed messages regarding “to shock or not to shock” in the hypothermic arrest. In one paragraph they state that it is ok not to shock (for the reasons above) but in the next paragraph state that 3 shock attempts (not stacked) is appropriate, then wait until T>30 before continuing. |

|

American Heart Foundation (2010)

In their 2015 update on cardiac arrest in special circumstances, the AHA did not update accidental hypothermia. Their recommendations is less comprehensive than the ERC and include:

|

(Rise in core temp per hour in brackets)

|

Passive

|

Active (External)

|

- Warm humidified gas via mask (1C) or ETT (1.5C)

- Warm fluids (42C) (doesn't increase core body temperature but does prevent cooling)

-

Body cavity lavage (from least to most change per hr)

- Bladder (< 3C)

- Gastric

- Peritoneal (3C)

- Intrathoracic (3-6C)

- RRT (Haemofiltration)

- CPB (9-18C)

- Extracorporeal (9-18C)

|

How To: Perform Thoracic Lavage

Plaiser et all describe one technique for Intrathoracic lavage;

"Two 36 French chest tubes were placed in each hemithorax. One tube was placed in the fourth intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line. Another tube was placed into the sixth intercostal space in the mid-axillary line. Sterile saline at 39.0◦C was infused by gravity into each superior chest tube and allowed to drain passively through each inferior tube." NB other's have documented the use of level 1 rapid infusers instead of gravity to increase the rate of rewarming

Reference

1. Plaisier, Brian R. "Thoracic Lavage In Accidental Hypothermia With Cardiac Arrest — Report Of A Case And Review Of The Literature". Resuscitation 66.1 (2005): 99-104. Web. |

ENOUGH IS ENOUGH

More recently, there has been evidence to show a correlation between initial K and mortality (NB limited association with pH and lactate). The ARC guidelines regarding avalanches state that patients are "unlikely to survive" with a K > 12.0 mmol/L. A few limited case studies have provided the evidence for some local guidelines to employ a K > 10mmol/L as unsurvivable and therefore not requiring re-warming to reassess (1-4). Given a few cases of K 10-12 mmol/L since then, the current generally accepted upper limit for stopping CPR without rewarming is K > 12.0 mmol/L (the ERC, AHA have not commented on this in their guidelines)(5,6).

1. Walpoth BH, Walpoth-Aslan BN, Mat- tle HP, et al. Outcome of survivors of acci- dental deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest treated with extracorporeal blood warming. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1500-5.

2. Mair P, Kornberger E, Furtwaengler W, Balogh D, Antretter H. Prognostic mark- ers in patients with severe accidental hy- pothermia and cardiocirculatory arrest. Resuscitation 1994;27:47-54.

3. Farstad M, Andersen KS, Koller ME, Grong K, Segadal L, Husby P. Rewarming from accidental hypothermia by extracor- poreal circulation: a retrospective study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:58-64.

4. Schaller MD, Fischer AP, Perret CH. Hyperkalemia. JAMA 1990;264:1842-5. 51. Wang HE, Callaway CW, Peitzman AB, Tisherman SA. Admission hypother- mia and outcome after major trauma. Crit Care Med 2005;33:1296-301.

5. Brodmann Maeder, Monika et al. "The Bernese Hypothermia Algorithm: A Consensus Paper On In-Hospital Decision-Making And Treatment Of Patients In Hypothermic Cardiac Arrest At An Alpine Level 1 Trauma Centre". Injury 42.5 (2011): 539-543.

6. Brown, Douglas J.A. et al. "Accidental Hypothermia". New England Journal of Medicine367.20 (2012): 1930-1938.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed